Break Point | Monthly Column

Mentorship, mischief, and the long road to autonomy

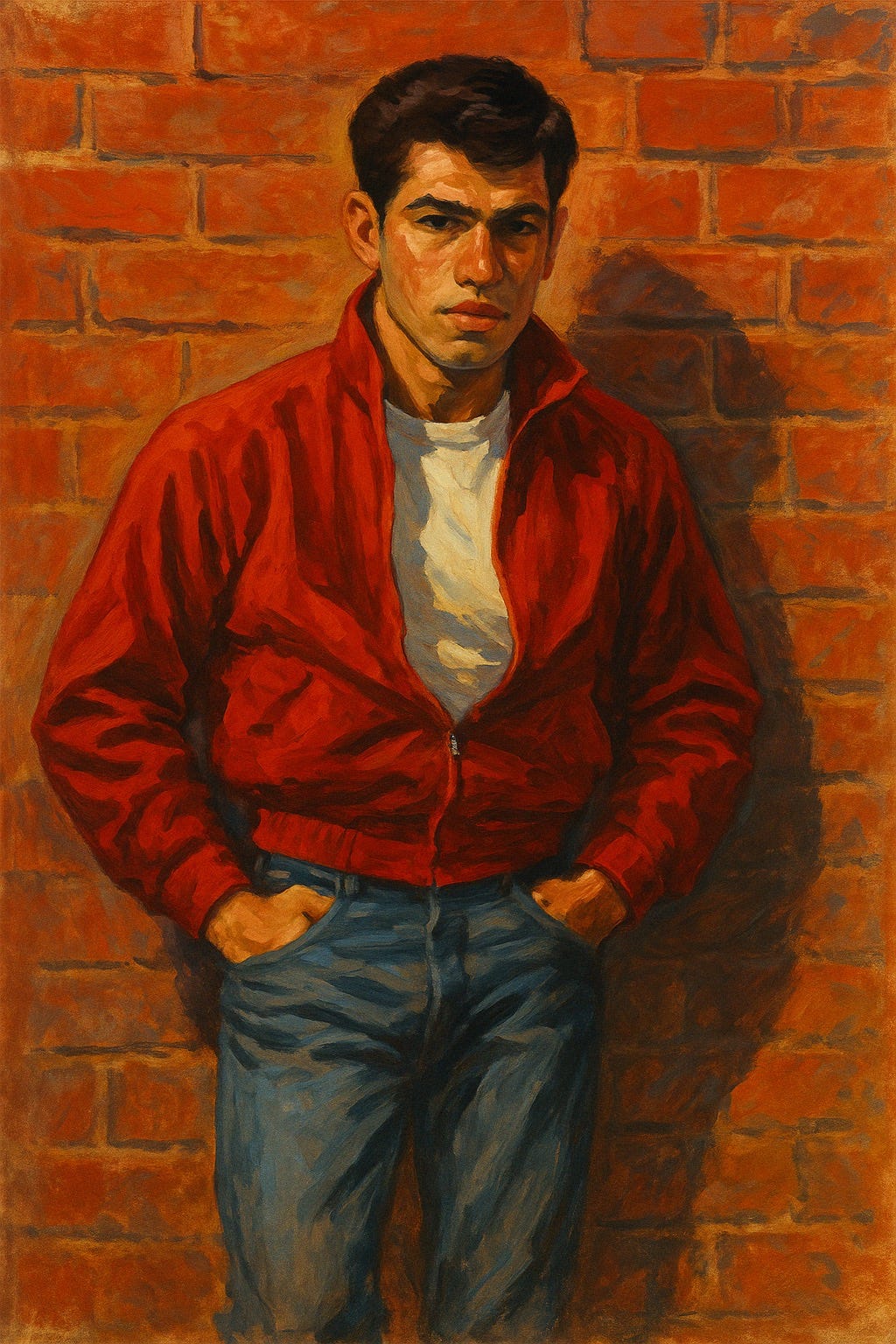

From James Dean to Juan Carlos

The drop shot wasn’t necessary. Not on break point, at 4–3, deep in the third set.

But that’s the thing with Carlos Alcaraz—it’s never only about necessity. The ball floated over the net like a dare, kissed the clay with a whisper, and left his opponent blinking. Then came the grin—part boyish mischief, part artistic pride. In an era of structured tennis systems and cold percentages, Alcaraz composes with flair. His joy isn’t strategy—it’s self-expression.

We’re watching a player who doesn’t just compete—he improvises. Not the messy kind, but the crafted spontaneity of a flamenco guitarist or a jazz soloist spiraling off the beat. Every rally is a jam session. He builds points the way Miles Davis built solos—with space, tension, and sudden bursts of brilliance.

No one else plays like this - not even Federer, whose grace echoed Brunelleschi’s dome. Alcaraz is more kinetic, more unstable. His genius lives closer to the edge. Federer floated. Alcaraz occasionally crash-lands. Federer was a finished cathedral. Alcaraz is still scaffolding—brilliant, raw, and exposed to the wind.

But artistry, as any painter or musician will tell you, comes with its own crucible: control. And now, the kid with the forehand that can part tennis courts is quietly learning the harder art—of becoming his own man. That process is never linear, and never quiet. Especially when it involves breaking ranks with the people who helped raise you.

The Mentor and the Mirror

Which brings us to Juan Carlos Ferrero.

For years, the Alcaraz–Ferrero relationship has been portrayed as one of harmony: the seasoned champion guiding the prodigious boy through the storm. But there’s a moment in every apprenticeship—quiet, necessary, and a little cruel—when the pupil begins to resist the hand that taught him. Not out of anger, but inevitability. A player starts to question.

And it has.

The centre, at some point, must shift. Something deeper is forming: a desire to own not just his shots, but his story. Like Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister, he’s no longer just following a path—he’s beginning to write it. The recent shift in his team is less a rupture than a rite: a young artist claiming space. This isn’t a rebel without a cause—it’s a young man searching for the right to choose his own.

Samuel López’s arrival doesn’t upend the foundation—it expands the ecosystem. Ferrero remains the central pillar, but López introduces a second current of thought, allowing space for options. For a player on the cusp of adulthood, it marks the quiet shift from being guided to learning how to choose. It allows Alcaraz to listen selectively, to weigh different insights, to begin shaping his own vision and making his own choices. It’s a smart evolution—not about replacing control with chaos, but creating more space within the structure. Less about deference, more about authorship and shaping the battle plan—on the road towards more independence.

Ferrero, to his credit, addressed the shift with honesty. Speaking about the new addition to their team, he said:

It’s a telling comment—not of conflict, but of awareness. Even the most successful dynamics eventually need space to breathe. Ferrero isn’t stepping aside, but stepping back just enough to let Alcaraz step forward. And he’s not alone in that belief.

Evolution, Not Erosion

This isn’t an erosion—it’s evolution. Darren Cahill, coach to Jannik Sinner, has long argued that new voices aren’t threats to progress, but preconditions for it. “Fresh perspectives, renewed motivation, different strategies”—these, he argues, are essential for longevity and growth at the top level. Over time, Cahill explains, relationships can shift from being about development to simply managing emotional needs or preserving the status quo.

And for a young player with ambitions beyond what he’s already achieved, status quo is the one thing that won’t do.

So this wasn’t rupture—it was an inflection point. A deliberate loosening of the reins. Alcaraz is no longer just a student absorbing wisdom—he’s a young man refining his own convictions. The new coach wasn’t brought in to fix a problem, but to support a transition: from prodigy under guidance to player in command. It’s the natural next movement in his composition.

The Risk of Growth

But growth carries risk.

Autonomy may enrich a player’s sense of self, but it can also fracture rhythm, disorient chemistry, and cloud instincts with overthinking. Sports and tennis history is littered with prodigies who took control too soon, only to find the game’s chaos less forgiving without a seasoned hand at the tiller. Nick Kyrgios, dazzling and instinctive, rejected traditional coaching—choosing flair over structure. The result was brilliance without direction, a career as marked by frustration as by flashes of genius.

Alcaraz’s joy may be pure, but it’s not immune to the consequences of solitary authorship. Genius can flourish with freedom—but it can just as easily flounder without guidance.

The sporting world rarely makes room for growing up. Sponsors expect results. Commentators demand polish. Fans mistake growth for regression. No one tells you that coming of age comes with a press conference. Every swing toward independence risks destabilising the very chemistry that made greatness possible.

Improvisation, Practised

This is the adolescent arc, playing out not in slammed doors or late-night phone calls, but in team dynamics, coaching tweaks, and the subtle choreography of independence. Alcaraz isn’t breaking from Ferrero; he’s quietly, and gracefully, stepping into his own light.

That doesn’t mean the joy is gone. But it’s changing.

Alcaraz used to play like a child set loose in a sweet shop: everything within reach, no consequences. Now, the joy is more considered. His shot selection is maturing, even if it still has that madcap edge. He’s learning that true freedom on court comes not just from risk, but from discernment. Improvisation, too, must be practised.

It’s a delicate balance—between instinct and structure, flair and discipline. Between Ferrero’s voice and his own. And perhaps that’s the most compelling story in tennis right now: watching a generational talent attempt not just to win, but to grow. Publicly. Emotionally. Tactically. Spiritually.

There’s a temptation to frame all of this in results: “He lost to Goffin in Miami, therefore the new coaching setup isn’t working.” But that would be missing the point entirely. What we’re seeing is the adolescence of a game, and of a mind. A player going through what every twenty-one-year-old does: the friction of self-definition. Only in this case, the stakes include stadiums, cameras, sponsorships, and a million unsolicited opinions from every quadrant.

And yet, the joy persists. That is the marvel. You just have to see the sheer joy and open natural smile after a magnificent shot in Barcelona.

Even in moments of pressure or tactical confusion, Alcaraz will try something outrageous—because he still trusts his instincts more than any blueprint. There is no fear of failure in his DNA. He seems to believe, earnestly, that the right shot is the one that feels true.

In this, he reminds us not of Federer or Nadal, but of something else entirely: a romantic, in the truest sense.

Still Becoming

But make no mistake—there’s iron beneath the smile. This isn’t just a boy wonder frolicking with drop shots. It’s a young man building an empire, one that he controls. The decision to bring in a new coach wasn’t about tactics. It was about agency. About saying, “I’m grateful, but I need to find my own rhythm now.”

That takes guts. Especially when the person you’re pushing against is your tennis father.

So where does this all go? Will Alcaraz’s game become more methodical, more Djokovic-like, as he seeks control? Or will he double down on flair and defiance, taking improvisation to ever-riskier heights?

We don’t know. And that’s the point.

He’s still learning where the lines are—when to play inside them, when to redraw them. His game is a living thing—shifting, stretching, mutating with every match. And if we’re lucky, we’re witnessing a kind of coming-of-age novel, written not in chapters but in service motions and forehand lobs on the court and on TV.

For now, Alcaraz remains the artist.

The court remains his studio.

And the masterpiece?

Still very much in progress.